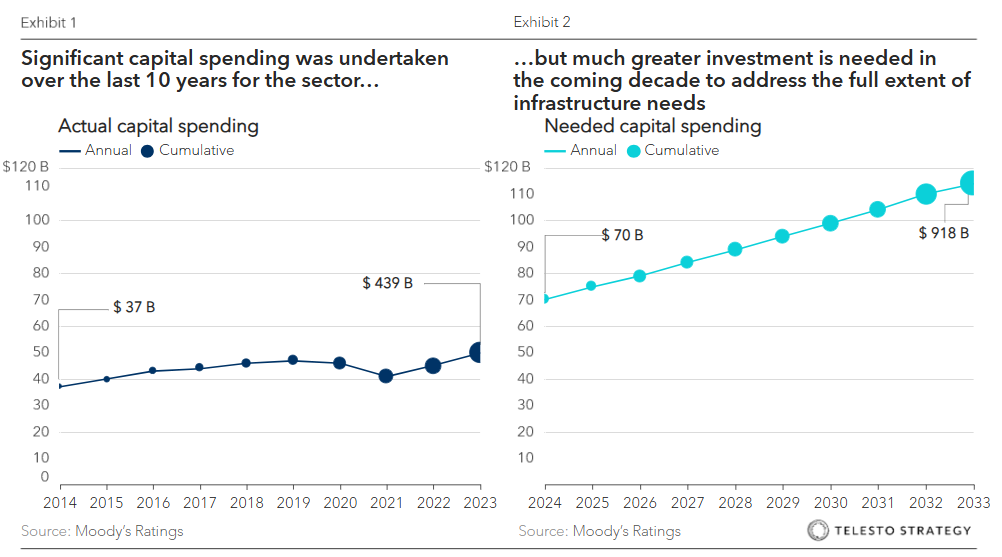

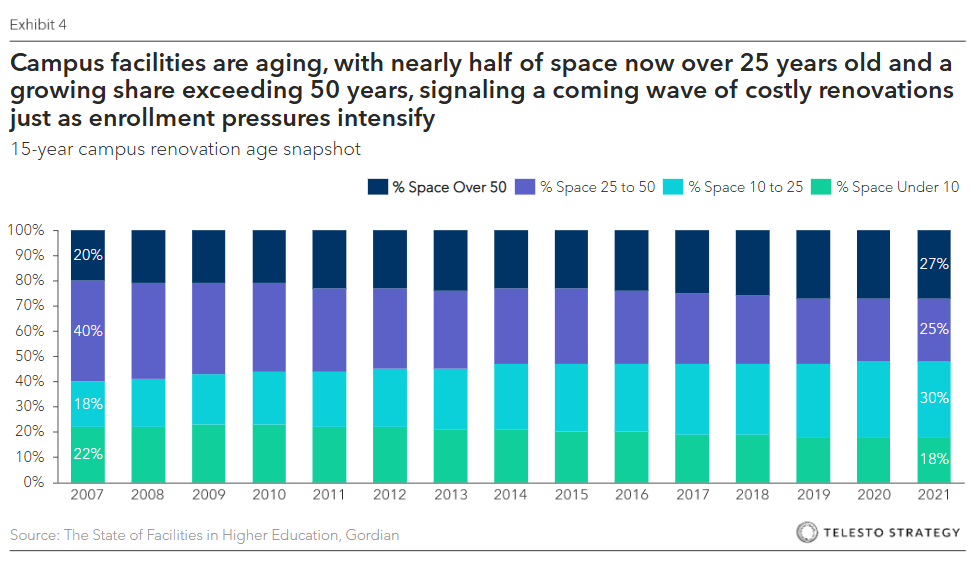

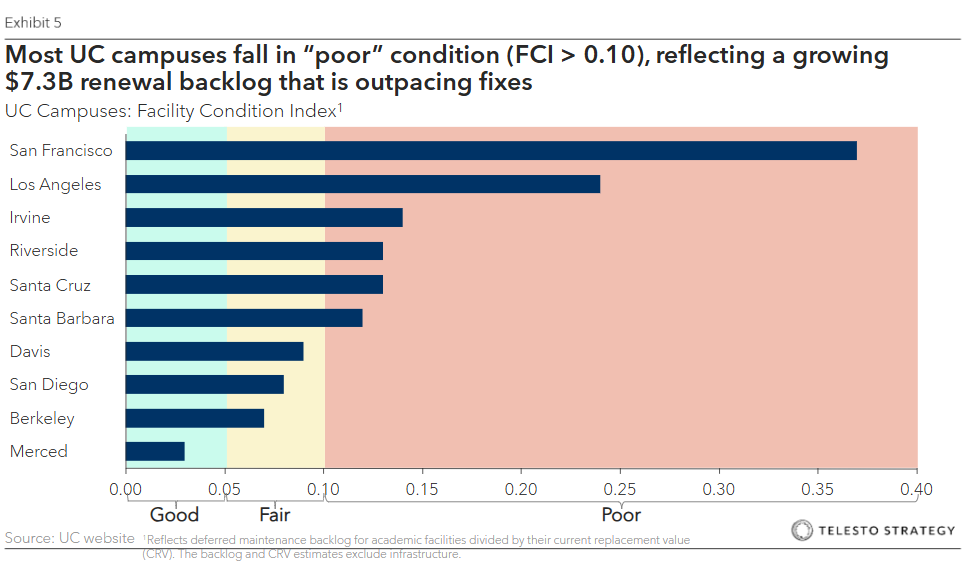

Deferred maintenance has evolved from operational challenge to enterprise-level risk. Collectively, U.S. colleges and universities face a staggering $112 billion in urgent deferred renewal needs, with Moody’s projecting $750–950 billion in spending required over the next decade just for rated institutions to modernize and stabilize backlogs. In a recent survey, 36% of chief financial officers (CFO) cite maintenance as a top risk. The average age of campus buildings is approximately 50 years, with many facilities already having surpassed their intended life spans. This aging infrastructure is reflected in Facility Condition Index (FCI) scores, where many systems report values greater than 0.10 — the commonly accepted threshold for “poor condition.”

The leadership imperative is no longer whether to act but how to sequence and finance renewal programs that protect budget, advance energy transition commitments and sustain institutional competitiveness.

Drivers of underinvestment

- Structural budget constraints and depreciation gaps. During downturns, maintenance is the first cut. From 2008–2013, virtually all spending categories in public higher ed grew — except operations & maintenance, which declined in real terms. Underfunding depreciation became a budget-balancing tactic

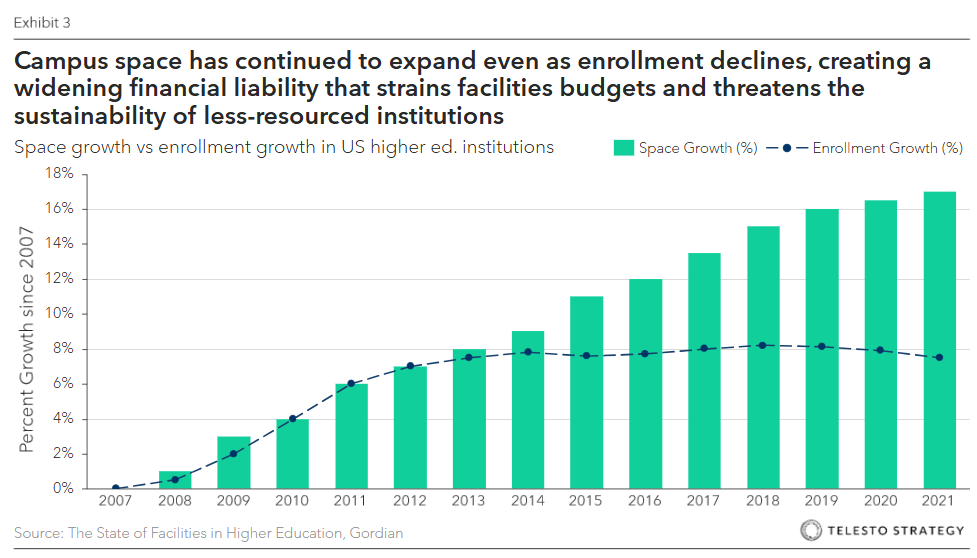

- Space growth outpacing resources. Campus footprints more than doubled since 1970 (+113%), while the college-age population grew just ~17%. More space plus older space—without matching O&M budgets—equals ballooning liabilities

- “Shiny new” bias. Donors and lawmakers prefer funding new buildings, not roofs or pipes. Capital projects win ribbon-cuttings; maintenance rarely does. This incentive gap diverts resources from renewal

- Short-termism over long term focus. Leadership turnover and budget stress drive reactive choices to defer costs for “just a few more years,” but small issues compound into major repairs, turning short term relief into long term liability

- Aging infrastructure wave. Two building booms — post-WWII/1960s and 1990s–2000s — mean assets are now hitting end-of-life simultaneously. Systems built 50–70 years ago need replacement, while 15–25-year-old facilities are due for major lifecycle renewal.

Cases in point

For many institutions, the real challenge isn’t enrollment or budget, it’s mounting operational strain:

- California Public Universities. Chronic underinvestment as left UC and CSU with $17.4B in deferred maintenance. Many campuses exceed FCI > 0.10, with aging systems and sprawling footprints. Without a long-term funding plan, the Legislative Analyst’s Office warns costs will balloon and disruptions will worsen.

- University of Massachusetts. UMass has built up $4.8B in backlog over a decade, driven by inconsistent funding and donor preference for new buildings over repairs. The result: inefficiency, higher costs, increased outages, and pressure on the student experience.

What good looks like:

- University of Nebraska. Facing an $800M backlog, Nebraska issued $400M in bonds (with another $400M planned) and mandated a 2% depreciation set-aside per project. This approach is projected to avoid $1.5B in inflation and emergency costs over 40 years, embedding fiscal discipline and ending crisis-driven funding.

- University of Virginia. With 70% of facilities over 30 years old, UVA secured recurring renewal budgets, reducing backlog from $196M (2009) to $134M (2016). By systematically reinvesting in critical systems and embedding renewal into the operating budget, UVA achieved sustainable outcomes.

- University of Maine System. Confronting >$1B in deferred maintenance, Maine adopted a “no net new space” policy — any new construction must be offset by demolition or repurposing. The rule halts backlog growth, controls O&M costs, and focuses capital on mission-critical facilities, reframing growth as quality over quantity.

Strategic implications:

- Credit and financial pressure. Deferred maintenance is a hidden liability. Moody’s estimates $750–950B is needed this decade. Reactive fixes cost far more than planned renewal, draining margins, straining debt capacity, and driving up insurance premiums.

- Reputation and competitiveness. Conversely, institutions with visible renewal projects improve student satisfaction and faculty recruitment. Infrastructure failures — leaks, outages, shuttered dorms — erode brand, deter students, and hurt recruitment. Visible renewal, by contrast, signals investment in quality and boosts satisfaction.

- Sustainability setbacks. Outdated systems waste ~30% of energy and lock in emissions, making carbon pledges unattainable and signaling carbon-intensive portfolios; deferred maintenance turns sustainability into a casualty of underinvestment, while visible action—like Michigan’s $300M in green bonds — strengthens credibility, reputation, and access to capital.

Resilience and compliance. Neglect heightens safety and accreditation risks. Proactive renewal reduces liability, ensures compliance, and protects institutional standing.

Actions higher education leaders can take:

- Establish baseline. Conduct comprehensive Facilities Condition Assessments (FCA), quantify backlog and FCI by asset class, and develop risk registers.

- Prioritize by risk and ROI. Sequence projects addressing both life-safety and efficiency (roofs, central plants, controls).

- Deliver quick wins. Implement LED retrofits and controls campus-wide; replace aging HVAC for ≥30% energy savings; reinvest savings in further backlog reduction.

- Develop a comprehensive financing structure. Use bonds, energy performance contracts, and green bonds to reduce WACC (weighted average cost of capital) and allocate savings for reinvestment.

- Adopt governance levers. Institutionalize no-net-new-space policies (UMaine) and 2% depreciation set-asides (Nebraska).

- Upgrade data and project management processes. Build asset registries and KPI dashboards; Improve preventive maintenance to avoid future backlogs.

Strategic questions for leadership

- What is our true backlog and FCI by asset class, and is it rising or falling?

- Which projects can reduce backlog and cut Scope 1/2 emissions ≥20% within three years?

- What annual reinvestment rate (% of CRV) will stabilize backlog growth at our institution?

- Which governance levers (no-net-new space, depreciation) will we adopt this year?

- What funding mix will we use in the next 24 months (bonds, performance contracts, green bonds), and what is our expected cost of capital?

- Do we have the team and partners to deliver at pace, and where do we need outside help?

- How will we prove progress each quarter (backlog dollars removed, energy saved, risks closed, student satisfaction)?

Deferred maintenance is a strategic inflection point, not just an operational challenge. Institutions that convert backlogs into sequenced, financed renewal programs will safeguard financial health, accelerate energy transition progress, and strengthen student experience. Planned renewal is more cost-effective than reactive repair, leading to fewer failures and reduced energy expenses. The question for leaders is not if but how quickly they will act to secure institutional resilience and competitiveness.

Our people

Andrew Alesbury

Partner, Washington DC

With a background spanning both urban planning and real estate development in the United States, Andrew supports sustainability and facilities departments across higher education institutions to develop and execute strategies which enable them to achieve their ambitions while navigating complex stakeholder environments and addressing student and faculty concerns.

Ben Vatterott

Partner, San Francisco

Ben has led sustainability and growth strategy projects for clients across the higher education and real estate ecosystems, including universities and colleges, private real estate companies, PropTech companies, and more. He supports clients on a number of strategic topics such as achieving net zero targets, embedding sustainability and emissions reduction into capital deployment, and capturing sustainable growth opportunities.