In the next decade, the most competitive companies will be governed not by the most prestigious resumes, but by boards engineered for complexity. U.S. boardrooms are re-skilling under pressure from four converging forces: (i) AI deployment and risk, (ii) supply chain and ESG regulation that reaches deep into suppliers, (iii) increasing geopolitical tensions, and (iv) heightened investor scrutiny of board capability, disclosure, and refreshment. In 2025 and beyond, governance sophistication is no longer optional – it is a determinant of market value, stakeholder trust, and competitiveness.

Key takeaways:

- Boards are reenvisioning what “qualified” means with the mainstreaming of skills matrices, technical reviews, and a push for composition that address dynamic areas of enterprise risk – AI, cyber, geopolitics, and ESG

- Director pipelines remain dominated by CEOs, CFOs, and industry operators. While invaluable for capital allocation and M&A, they may be insufficient for technology governance, sanctions exposure, data risk, sustainability, or climate transition

- Certain compliance regimes explicitly or effectively require board training and upskilling, with financial and other liability penalties

- The fastest-moving boards are treating training as infrastructure and build cross-functional oversight muscle to improve governance under uncertainty

The World Economic Forum places cyber, conflict, climate, and tech-related threats among the most salient near-term global risks, underscoring how these domains interlock and self-perpetuate. Similarly, geopolitics has outgrown the investor-relations department given increasing sanctions, export controls, tariffs, logistical chokepoints, outbreak of armed conflict

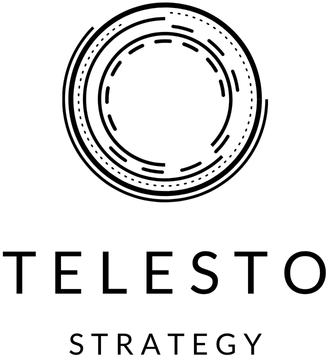

Yet, at the same time, in 2025 PwC reports that directors still over-index on traditional expertise and director pipelines remain dominated by former CEOs, CFOs, and industry specialists. However, this hasn’t necessarily fostered confidence across board cohorts; more than half of corporate directors think at least one director should be replaced and that assessment processes often fail to surface skills gap.

The CEOs are seeing the gap. Comparative survey data underscore just how much the baseline has shifted. In the Spencer Stuart 2025 U.S. Board Index, while only 22% of CEOs say their boards were effectively supporting companies through today’s challenges, board turnover remains stubbornly low—now estimated at 7% of seats annually.

The conversation is moving beyond who sits in the chairs to what the board can actually do—to oversee AI at scale, supply chain accountability, geopolitical, ESG, and cyber-resilient operations. Investors are no longer satisfied with labels; they want evidence of capability and process. Boards that tie composition to strategy, codify oversight in charters, elevate disclosure quality, and refresh with intent will be better positioned to defend margins and seize opportunity in 2026.

Agenda complexity mounts

Directors report rising agenda complexity, yet board refresh lags. Nearly 75% of directors have shown this in recent NACD research—they respond that both the number of topics on the board agenda and the number of issues that individual directors must monitor have increased. Likewise, survey data shows that the time commitment of an independent director has increased over the years, from an average annual commitment of under 250 hours in 2015, to nearly 300 hours in 2025.

Harvard Law School’s Forum on Corporate Governance summarizes the dynamic well, “the role of a corporate director has never been more challenging — or more critical.”

Companies like to niche expertise to fill in the gaps

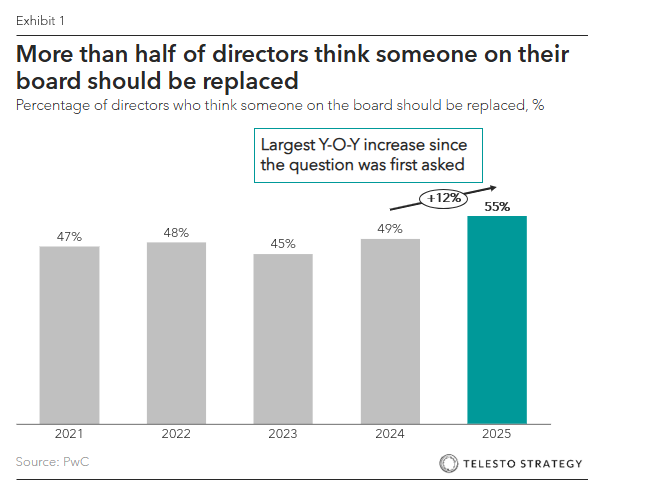

With such complexity, business leadership is being redefined for the operating environment of Q4 2025 and beyond. Strategic and leadership instincts are less universally applicable than before, in a world where revenue generation potential and risks are deeply tied to areas like rapidly evolving technology, regional or geopolitical tensions, supply chain, and divergent climate and ESG regulation.

Companies seek to fill these gaps by looking for more specialized background. More than two-thirds of directors interviewed indicate their board is more likely to seek out an individual with specific expertise than someone with general business leadership when filling the next board seat. Technology expertise is at a premium, alongside industry-specific background, ESG and climate, and geopolitical and geoeconomic domains.

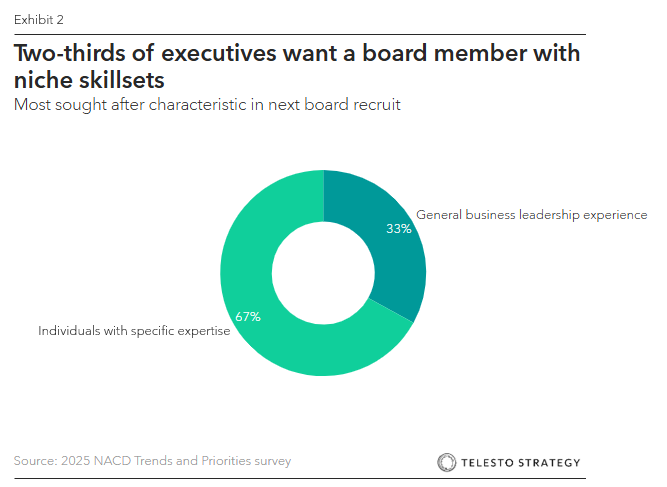

Boards adopt skills matrices

With board composition and process as strategic levers, leading boards are adopting skills matrices that map expertise across cyber, ESG, AI, and geostrategy – then linking that map to refresh priorities, committee charters, and training agendas. Others are introducing AI assurance frameworks, integrated resilience metrics, and dedicated geostrategy sessions to embed foresight into the board calendar.

What doesn’t work well in designing and adopting a skills matrix? First, is treating the matrix as a compliance checklist. Common failure modes include: very long lists of generic competencies where nearly every director is marked as “expert” in nearly everything; no visible linkage to the company’s top strategic and risk exposures; and matrices that are static year-to-year and never referenced in succession planning or evaluation. Morever, the matrices should serve as a foundation for individual self-assessments and external benchmarking.

Notable examples include:

- ANZ and Westpac (Australia). Each maintain and disclose board skills matrices in their corporate governance statements. Both explicitly reference cyber, ESG, and other risk-relevant domains, and use the matrices to inform candidate selection and board renewal over time

- Haleon (Europe). In its 2024 Annual Report, target boards skills are highlighted to assess and strengthen its FMCG, financial, and digital expertise. While the matrix itself is not disclosed, the company actively reviews and updates its board skills matrix.

- Bakkavor (Europe). Reports using a structured self-capability assessment to populate its group board skills matrix and guide succession planning.

- Unilever (Europe). Was recognized for comprehensive disclosure built around its board skills matrix, linking financial and non-financial oversight capabilities.

- Coca-Cola (U.S.). Although not always a full “matrix” published annually, Coca-Cola is cited by proxy advisor analyses as an early adopter of board skills disclosure and matrix formats. In a layered approach, its skills assessment summarizes the qualification of board nominees and includes additional breakdowns of membership by independence and tenure.

- Microsoft. Has begun linking board skills and expertise to dynamic strategic domains (AI, cyber, global operations) even if they may not publish a full tick-box matrix.

Figure 3. Example board competency matrix

As illustrated above, Europe and Australia have taken a lead in integrated the disclosure of board competency matrices. The UK’s comply-or-explain governance tradition and the EU’s emphasis on ESG, risk governance, and transparency have pushed large corporates to codify board capabilities openly. In contrast, many U.S. companies remain less consistent in format—with some using narrative descriptions or a more consolidated tabular view.

Training considerations and other activities to improve board effectiveness

Companies are increasingly designing highly tailored training programs targeted at board members to fill these emerging competency gaps, especially in AI, in an array of formats – blended online and in-person modules, simulations, case-studies of breach response or AI failures, peer-to-peer learning, and even role-play of cyber crises.

By linking training to identified capability gaps in the board matrix, the nominating and governance committee can show progress and accountability in upskilling the board. Moreover, certain compliance regimes explicitly or effectively require board training and upskilling:

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Cybersecurity disclosure. Requires public companies to disclose the board’s oversight of cybersecurity risk and management’s role in identifying and managing threats

- EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). CSRD explicitly requires companies to report how administrative, management, and supervisory bodies contribute to sustainability oversight, including expertise and training. Annex and ESRS 2 disclosures require entities to describe board competencies in sustainability matters and training mechanisms implemented to ensure ongoing capability.

- EU Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act). The EU AI Act (formally adopted in 2024) introduces obligations for providers and deployers, especially where high-risk AI systems are used (e.g., HR, credit, healthcare, safety). Governance requirements include risk management, data quality, human oversight, monitoring and incident reporting. Boards will be held accountability for failing to understand and govern AI.

- UK Corporate Governance Code. The 2024 revision reinforces responsibilities of board skills, expertise, training, and time commitments, requiring disclosures on how the board ensures it has appropriate knowledge and development. Annual reporting must show how directors have updated their skills and knowledge and how the board evaluates effectiveness.

- Australian Securities Exchange CG Principles. Explicitly requires listed companies to disclose a board skills matrix, and commentary from the ASX Corporate Governance Council and the Australian Institute of Company Directors emphasizes that ongoing development is necessary to address gaps.

- Data protection. GDPR, CCPA. Data protection regimes create indirect training mandates because boards must oversee data protection officers (DPOs), breach procedures, and compliance architectures. Boards must understand privacy risk, vendor management, cross-border transfers, and enforcement exposure—or face civil penalties and shareholder action.

Actions boards can take:

- Run a “composition-to-strategy” review. Link the three-year plan to required board competencies (AI at scale, digital operations, value chain due diligence, climate and nature risk, cyber resilience). Update the skills matrix and publish it.

- Treat supply chain risk as a board topic. Request a UFLPA and EUDR readiness dashboard: supplier mapping depth, geographical coverage, data confidence, corrective-action workflow, and incident metrics (detentions, cycle-time, financial impact). Schedule regular pre-mortems on high risk categories.

- Institutionalize and disclose director education. Commit to a structured curriculum (AI safety, assurance, model risk, supply chain law, ESG, climate and nature disclosures) with external briefers, peer-to-peer learning, and site visits to key suppliers or labs—documented in the proxy.

- Design AI oversight explicitly. Put AI risk and assurance into a charter, name a management owner, adopt principles for responsible AI, and ensure periodic board-level reporting.

Questions for the boardroom:

- Does our current skills map credibly cover AI, ESG, geostrategy, and cyber risk at the committee level and in aggregate? Where are the hard gaps? What is the timeline and process to closing them?

- Where do we run high-risk AI systems, and how will EU AI Act obligations flow through our supply chain and product lines by 2026-2027?

- Which chokepoints, sanction pathways, potential or existing armed conflict, or political events could threaten our top three revenue engines, and what contingencies are in place?

- Are ESG and climate questions being discussed with the same discipline as audit and compensation? Is the board receiving decision-grade dashboarding in addition to the narrative reports?

- How can training programs provide support for directors to improve their ability to oversee, as opposed to make programmatic or management-level decisions?

Additional Telesto resources:

- Atlas, equips your organization’s corporate directors and leaders with the insights and knowledge necessary to stay up to date, mitigate risks, and seize business opportunities associated with sustainability, climate, and ESG

- Prism, our ESG benchmarking tool, helps your organization to rapidly strengthen its Sustainability, Climate, and ESG performance and disclosures through in-depth benchmarking of industry peers and identification of gaps and areas of distinction

- Board series: The kitchen sink committee – AI, Cyber, ESG, and now tariffs. Are Audit Committees ready?

- Board series: The CEO confidence gap – How can boards step up in a context of global uncertainty?

- Board series: Entering the Quantum Economy – What boards need to know in 2025