Over the last two years, the AI conversation in boardrooms has shifted from “What is this?” to “How can we best deploy?” The next wave for early adopters is to advocate for including AI agents as de facto members of the board – embedded in the board portal, continuously scanning risk, proposing agenda items, and generating draft resolutions. For large multinationals, the question is no longer whether AI will set in the boardroom - it already does. The question becomes, how far should boards go in treating AI systems as quasi-members of the governance team? And, what does it mean for fiduciary duty, legal liability, and board dynamics?

Key takeaways:

- Today’s laws still expect human directors, be it corporate law regimes in Delaware, UK, Germany, Hong Kong, that require supervisory board members to be “natural persons,” thus effectively barring AI from being a legal director today

- Boards are using AI as tools, not fiduciaries. Around 60-70% of boards report using AI to support governance work and strategy discussions with no indicating of granting an AI voting rights

- Shadow AI governance is the bigger risk, as AI systems may heavily shape analysis, risks prioritization, and wording of disclosures, yet legal accountability remains with human directors and officers

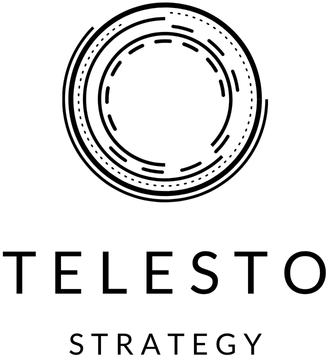

- Over time, AI adoption will evolve from tools, to advisors, and then institutional infrastructure

The current lay of land

A handful of headline-grabbing experiments have fueled this narrative. A Hong Kong venture capital firm famously appointed an algorithm, VITAL, as a board member in 2014. Like other members of its board, the algorithm was granted voting rights on whether the firm makes an investment in a specific company Chinese gaming company NetDragon Websoft appointed a virtual AI “CEO,” Tang Yu, to help run a subsidiary in 2022. And in 2025, surveys show that roughly two-thirds of board professionals are already using AI tools for board work, even if not granting them formal status.

The more meaningful trend is not agents on the roster, but AI woven into how boards work and a recurring item on the board’s agenda.

What the law currently allows

For large multinationals, the binding constraint is not imagination; instead, it is the contours of corporate law that assumes directors are human.

- U.S. (Delaware). Delaware General Corporation Law 141(b), the template for many U.S. public companies, states that “the board of directors of a corporation shall consist of 1 or more members, each of whom shall be a natural person.”

- United Kingdom. Section 155 of the UK Companies Act 2006 requires every company to have at least one director who is a natural person, and related reforms have tightened the use of corporate directors.

- Germany. Under the German Stock Corporation Act, members of the supervisory board must be natural persons with full legal capacity.

- Hong Kong. Hong Kong’s Companies Ordinance requires at least one natural person director and restricts corporate directorship in listed groups.

At the same time, legal scholars engage in active debate on whether AI systems could, in future, be granted some form of legal personhood similar to corporations, which would open the door to more formal roles in governance.

How leading boards are evaluating their options

In practice, large multinationals are framing AI in the boardroom in a staged redesign, not as a single leap to agent directors. In the near term, the emphasis is on AI literacy for directors, establishing basic guardrails, and embedding AI within existing committee structures (chiefly in audit, risk, and technology. Soon thereafter, companies have plan to evolve their AI tools into an always-on board analyst—a persistent “board agent” embedded in board portals that remembers past resolutions, detects inconsistencies, proposed agenda priorities, and supports on scenario analysis on strategic questions. Over the longer-term, leading companies will have institutionalized AI governance with dedicated oversight structures, model assurance processes, and consistent disclosure (similar to current day cyber and climate disclosure protocols).

For certain boards, the pace may be more accelerated as the upside of AI-augmented decision-making is too large, and too visible, to ignore.

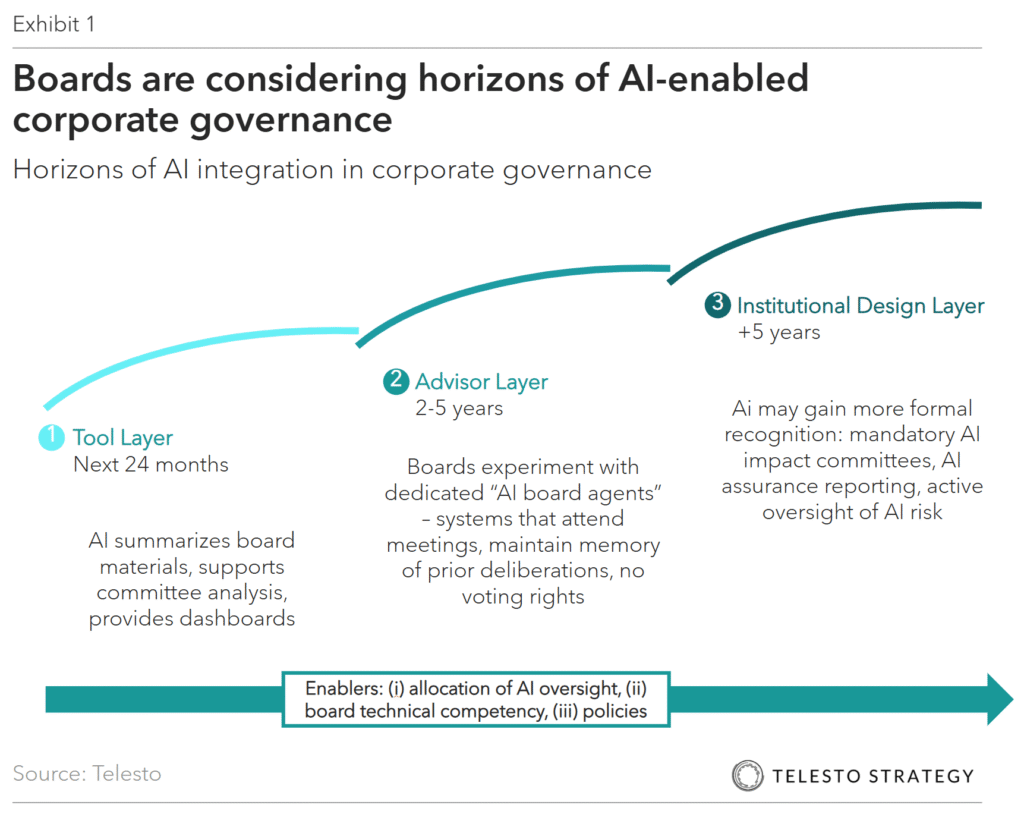

Where is AI oversight currently?

In 2025, the primary oversight of AI in large U.S. multinationals sit in a hybrid space between the full board and its key committees. PwC’s 2024 Annual Corporate Directors Survey found that 57% of directors say the full board has primary oversight of emerging technologies like AI, while only 17% assign that role to the audit committee.

However, disclosure data from large issuers shows a pivot toward formal committee ownership: 48% of companies now highlight AI in the risk-oversight section of their proxy, up 16% from the year before. Moreover, 40% explicitly charge at least one board-level committee with AI oversight, up from 11% in 2024.

Like most emerging areas of risk and compliance, the audit committee once again emerged as the default home for AI oversight. The driving factor seems to be in the framing of AI as controls, disclosures, and a risk management issue akin to cyber, ESG, or financial reporting.

As we think to 2026 and beyond, we expect to see a shift from today’s mixed “full-board-plus-whoever-is-interested” model to a more coordinated framework with audit as primary, and technology and nom-gov committees as secondaries. For long-term value creation, the full board will still be responsible.

How are boards meeting the moment?

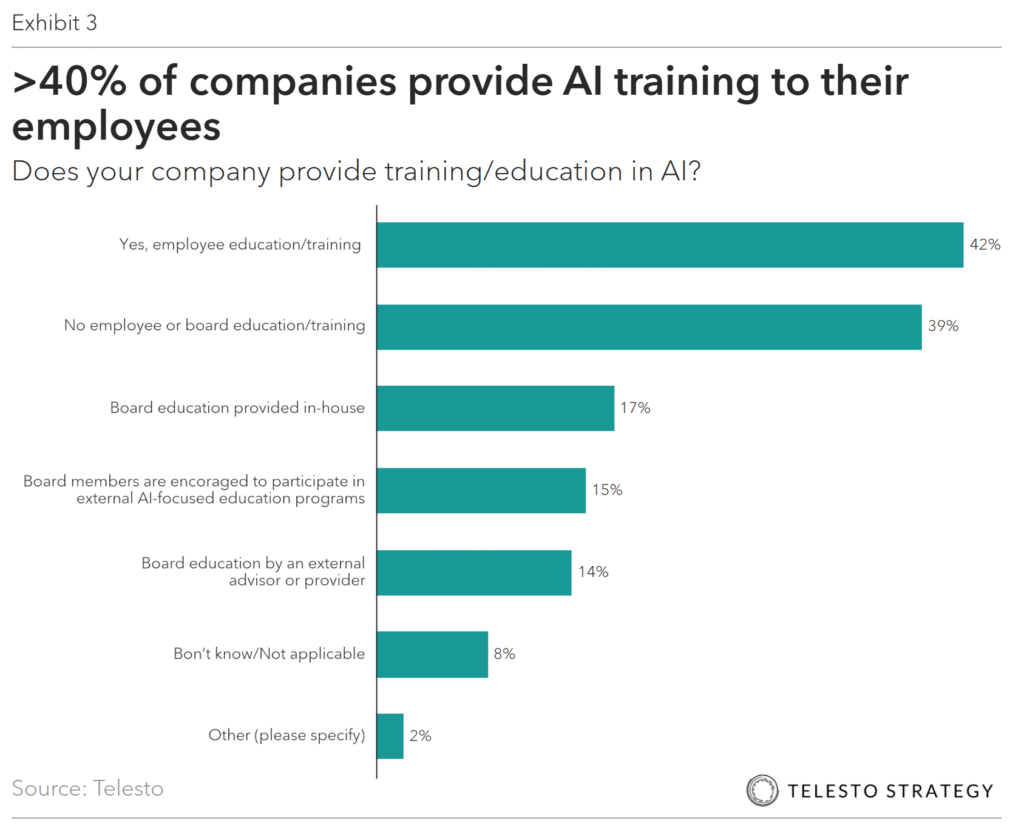

Boards are entering a new era of AI accountability. To rise to this occasion, large boards, especially those of Fortune 500 companies and other large multinationals, are placing a high priority on training directors to oversee AI responsibly and strategically — especially in the context of AI becoming a core governance issue rather than just a technical one.

Despite new training programs, a recent analysis finds that only 35% of boards have fully incorporated AI into their oversight role, and roughly 38% of directors feel they don’t receive sufficient AI education. This education gap will be one to watch for 2026, especially as liability and litigation will increase in legal gray areas with AI implementation.

Actions boards can take:

- Declare a principle: AI as a tool, human as fiduciaries. Updated board charters and governance guidelines to affirm that only natural person directors exercise fiduciary duties and voting authority—while explicitly permitting AI use as a decision-support layer.

- Map where AI is already in the boardroom. Ask management and the corporate secretary to inventory all uses of AI in board and committee workflows (pack preparation, analytics, minutes, disclosure drafting) and identify high-risk touch points.

- Assign clear oversight. Decide which committee(s) own AI oversight—often a combination of audit and risk (controls, assurance), technology (architecture, vendor risk, and compensation and nom-gov (talent, board composition). Ensure their charters explicitly reference AI.

- Set standards for AI “board agents.” Before adopting any persistent AI assistant in the board portal:

– Define its permitted and prohibited uses

– Require transparency on training data, model lineage, and update cycles

– Mandate robust access controls, logging, and incident response plans

– Require that key outputs b reviewed and validated by humans - Upgrade director literacy and stress-test culture. Arrange briefings and trainings on AI capabilities, limitations, and legal implications.

Questions for the boardroom:

- Status and strategy. Where, specifically, is AI already influencing our board’s decisions—directly or indirectly?

- Legal and fiduciary. Are we confident we understand the legal limits in our key jurisdictions regarding AI and directorship, especially given our incorporation structures? Is this reflected in our charters?

- Data, bias, and narrative integrity. How do we detect and address bias in the AI systems that support our strategic decisions? Are our AI-generated or AI-assisted statements (e.g., ESG, climate, AI, ethics, risk disclosures) aligned across reports, websites, and internal communications? Or, are we accumulating narrative contradictions?

- Talent and composition. Do we have enough AI literacy on the board to challenge management and vendors? Or, do we need to adjust composition, bring in advisors, or create an AI advisory council?

Additional Telesto resources:

- BoardCollective by Telesto, is an exclusive resource dedicated to providing targeted sustainability training, insights, and resources to current and aspiring board members

- Prism, our ESG benchmarking tool, helps your organization to rapidly strengthen its Sustainability, Climate, and ESG performance and disclosures through in-depth benchmarking of industry peers and identification of gaps and areas of distinction

- Board series: The kitchen sink committee – AI, Cyber, ESG, and now, tariffs. Are Audit Committees ready?

- Board series: Markets moving faster than board skills – Facing the hard reality of AI, ESG, supply chain, and cyber